HOW TO STUDY AN

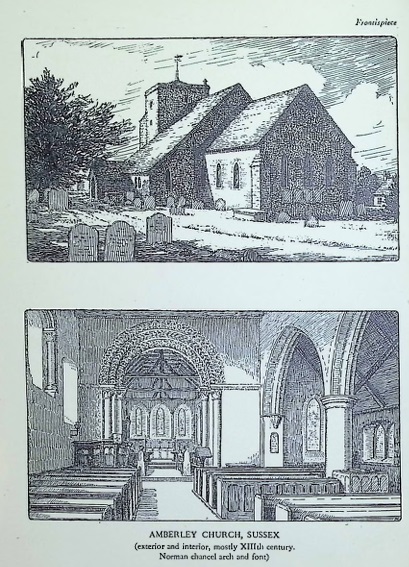

OLD CHURCH

By

A. NEEDHAM, F.R.S.A., A.M.C.

With an Introduction by

J. LITTLEJOHNS, R.L, R.B.A., R.C.A.

With 450 drawings by the Author

B. T. BATSFORD LTD.

15 NORTH AUDLEY STREET, LONDON, W.i

AND MALVERN WELLS, WORCESTERSHIRE

First published Summer 1944

You have wandered round this ancient church and have enjoyed

the peace and rest of its atmosphere.

Did you think, as you looked at the font, of the many thousand

children who have been admitted here into the membership of the

Church ?

As you stood before the Lord’s Table, were you one, in imagination, with those innumerable men and women who in every

generation have here received Christ’s special blessing?

Our forefathers first built this church and then maintained it

with care and devotion.

It is now our heritage and our responsibility. It demands our

unceasing service for its maintenance and repair.

Will you help us by playing your part?

Notice in Hawkhurst Church, Kent (slightly adapted).

MADE AND PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN

BY T. AND A. CONSTABLE LTD. AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, EDINBURGH,

FOR THE PUBUSHERS, B. T. BATSFORD LTD.,

LONDON, AND MALVERN WELLS, WORCESTERSHIRE

FOREWORD

The majority of small guide books to old churches previously

published describe them by means of much letterpress accompanied

by few illustrations. This book reverses that policy. It is arranged

to impart information at a glance, by means of a large number of

illustrations. Visitors to churches should be able, by reference to

these illustrations, to recognise all objects of interest. Attached to

each page of illustrations are brief notes, while the other pages

contain fuller details, under various headings for easy reference.

The information in this book is intended for those who like to

look at our old churches, but have not time to delve deeply into

church history and architecture. All interesting facts are presented

as briefly as possible.

With the exception of stained glass, which requires colour to

portray it, and church plate, which is not usually accessible to the

ordinary visitor, the illustrations, drawn from a large number of

churches visited, show virtually all the objects of interest. No

one church will contain them all, and some have only few, chiefly

owing to destruction by 16th century Reformers and 19th century

restorers, but visitors can, with the aid of this book and a little

imagination, picture the appearance of our churches in Medieval

Times, when they were filled with treasures of craftsmanship of

which only some remain.

The illustrations, with some exceptions referred to below, are

intended to convey a general impression of each object, as, owing

to the small size of many of them, due to the large number included

on each page, minor details had to be omitted. It has also been

impossible to avoid in the setting out of the illustrations, some

discrepancies of scale, in order that the smaller subjects can be

reproduced to an intelligible size. It must be understood that

the exigencies of space have necessarily caused the drawings to

be set close together, and I have not hesitated to sacrifice appearance to comprehensiveness, which I have felt was the most important factor, and I do not think that the inevitable crowding

of the subjects is an overwhelming disadvantage. To facilitate

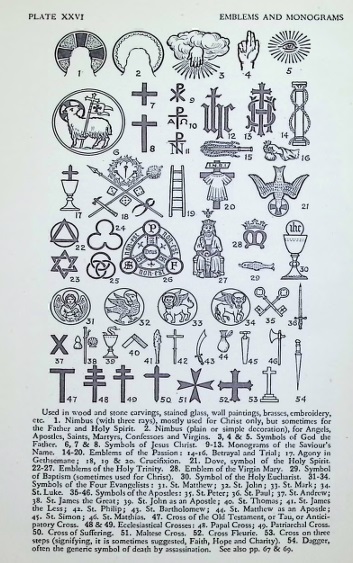

their use as references, the head-coverings on Plate XVII and the

emblems, etc., on Plate XXVI are drawn in outline only, as small

perspective drawings in light and shade would hide some of the

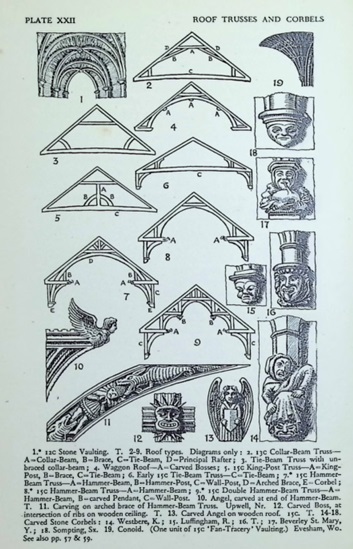

necessary details. The plans, roof trusses, and arches, on Plates

IX, XXII, and XXIII, are diagrams to illustrate the gradual development of these forms.

The book is largely self-indexing according to the grouped

subjects shown in the Contents, and it is felt that in a concise

handbook there is no occasion for an extremely long Index. The

main subjects have, however, been included in the brief Index at

the end.

For those who wish to use the book as a guide to the original

objects from which the drawings were made, in order to study in

detail the beauty of the craftsmanship that the small size of the

illustrations makes it impossible to convey, the names of the

churches containing them are given as far as is possible. Unfortunately some of the sketches, which were made over a period

of many years, did not contain a note of the building, and memory

has failed to recall, in every such case, the name of the church,

but a number of these are typical examples to be found in many

churches.

The Introduction and Explanatory Remarks on pages 1 to 6

should be read before visiting the churches.

The author is deeply grateful to Dr. John F. Nichols, M.C.,

F.S.A., Hon. Director of the British Archaeological Association,

for his kindly interest and his invaluable advice.

A. N.

Haywards Heath,

Sussex.

INTRODUCTION

A few general remarks may be helpful to the reader before proceeding to the notes and illustrations.

To appreciate fully the beauties of our churches it is essential

to keep in mind the position they occupied, the purposes they

served, and the influence they wielded in Medieval Times.

They were not built only for worship at regular intervals, with

occasional services such as christenings, marriages and burials,

remaining empty more often than not; on the contrary, the parish

church was the centre of local communal life.

It was supported by all; it relieved the sick and needy; it was

used as a parish hall; the church house was the meeting-place of

the guilds; and even ale was brewed on the premises, sold for the

church funds, and drunk during dances and fairs in the churchyard.

The sexton, parish clerk and the churchwardens were far more

important persons in those days. The sexton acted as a kind of

town-crier proclaiming the obits and masses for the morrow. The

parish clerk assisted the parish priest, when Mass was said daily.

He rang the bell, prepared the altar, led the responses, and preceded the procession with holy water. When the priest visited

the sick the parish clerk led the way and carried the bell and candle.

On Sundays and great Feast Days he went round the parish, entered

the houses, and sprinkled the people with holy water.

The churchwardens were entrusted with more varied duties

than to-day. They had to keep accounts of everything connected

with church funds, collect rents of lands and houses left to the

church, farm the church stock of cattle, sell wool and cheese and

gifts in kind made to the church, organise ‘Church ales’ and ad

minister the funds for the relief of the needy, church repairs, etc.,

prosecute such offenders against the ecclesiastical law as adulterers

and Sabbath-breakers; they also acted as bankers and pawnbrokers,

the valuables entrusted to them being stored in the church; they

were responsible for the safe custody of the Maypole, and of bells

and coats used in the Morris dancing. After the Reformation they

had many civil duties to carry out, such as the provision of arms

for the Militia, relief of married soldiers, provision of pounds,

stocks and pillories, and the destruction of vermin.

It must be remembered, too, that the church was often a place

of refuge against marauders, which sometimes accounts for the

thickness of the walls and the smallness of the windows, and the

position of the church on the highest ground. Sometimes it served

as a shelter from the blasts of the storms.

Facts such as these, as will be seen later, reveal the significance

of many features of a church which would otherwise be of no

interest and might often be unnoticed. We cannot appreciate the

fragments that remain unless we can realise the full extent of their

ancient glories.

The Medieval Church was full of colour. The fragments help

us to imagine the effect of the mural paintings, sometimes of great

dramatic intensity, which covered the walls, the beautiful stained

glass windows, and the brilliance of the brightly coloured and

gilded carving. These formed the background to an elaborate

ritual with images, candles, banners, and priests with their splendid

vestments—experiences of moving beauty.

Compared with their original state, our churches appear cold

and bare after the ravages of time, and man. Stone has crumbled.

The living form of the creators has often been renovated tastelessly or replaced by incongruous substitutes. With the coming

of the Renaissance and its intellectual, religious and political upheavals the Church lost much of its ascendancy and the buildings

were denuded of much of their beauty. But in spite of all the

ravages there still remains a glorious heritage—evidence of

triumphant strivings to create things of beauty for a lofty purpose.

In attempting to appreciate these remains we need to remember

that many of the churches lack the symmetry and consistency of

their originals because each succeeding period of building, in re

pairing or extending the old, used its new architectural style.

The Black Death, that great plague of a.d. 1349-50, which

carried off about a third of the population, put an end to church

building for a time. Later, a great religious revival, and the doctrine

of Purgatory, formed important motives for building and rebuilding

of churches, and for nearly two hundred years few remained untouched, while over 1000 were rebuilt from the ground.

Thus a church originally Saxon may contain parts of every

later period—a Norman tower and font, a 13th century sedilia, a

14th century doorway, windows in every Gothic style, and a

Jacobean pulpit, with later tasteless accretions descending to the

most modern misfortunes. With a little knowledge of the evolution

of architectural styles, as given in this book, we can sometimes see,

in one building, birth, rise, fall and decay extending over more

than a thousand years.

One of the first questions the uninitiated visitor asks is ‘How

old is this church?’ It should be unnecessary to say that a state

of natural decay, especially of the exterior, is less often an evidence

of the age of the building than of the nature of the stone. Flint

and granite are almost changeless; sandstone may soon crumble.

The visitor to a church of comparatively recent date (say 15th

century) may be looking at an exterior which has been wholly

restored, some of it two or more times, and yet it is in an advanced

state of decay. Or he may find in parts of our most ancient churches

stones which are just as they were when the buildings were erected.

There is a good deal of false sentiment about the prevalent

delight in decay. Actually a well-restored exterior may give a far

better opportunity to realise how the building looked when in its

perfect state. This, however, seldom applies to the decorations.

The modern restoration may be more mechanically skilful, but

the copy lacks the personal expression of the original.

Usually we have to go inside the church to find original work

in much the same state as when it left the craftsmen’s hands. This

applies especially to wood carving, where the marks of the chisel

are sharp and clear after the passage of five or six hundred years.

Apart from the misleading evidences of decay, the age of a

building cannot always be determined by a knowledge of historic

styles, because there have been two periods of Gothic revival—

a small one in the 17th century and a much more considerable

one in the 19th century. But neither movement very greatly

affected the rural areas, because new churches were seldom called

for in the depopulating villages, though a number were erected.

Speaking generally, however, the style of architecture tells, within

about fifty years, when any part was built.

The whole evolution from Saxon to Perpendicular, i.e. from

the 7th to the 16th centuries, can be divided into fairly well-marked

periods, joined by transitions from one period to the next. The

dates of each period cannot be stated precisely because the changes

did not take place at exactly the same time in every part of the

country. But in round figures it is a sufficient indication to divide

the periods thus:

INTRODUCTION

Saxon 7th century to 1060

Norman and Transition 1060-1190

Early English and Transition 1190-1300

Decorated and Transition 1300-1375

Perpendicular and Transition 1375-1550

The changes of style are to be seen to some extent in every aspect

of construction and decoration—plan, roof, tower, arches, windows,

mouldings and decorations. But the only safe guides are the

details and decorations. Square-headed windows are characteristic

of the latest period but sometimes occur in earlier ones. There

are many exceptions to the plans associated with each period. The

shapes of arches are not a safe guide, because they sometimes vary

in most periods in accordance with constructional needs. But the

changes in the shapes of mouldings, arrangement of tracery, carved

patterns and foliage have evolved consistently.

Those of us who visit many churches come across curious and

exceptional features for which general information provides no

explanation. These are more likely to occur in out-of-the-way

places where the craftsmen may have been less acquainted with

prevailing ideas. In many churches booklets are obtainable for a

few pence, and the county archaeological society can supply

information. The writers hope that the necessarily abbreviated

notes accompanying the following illustrations will stimulate many

readers to pursue their enquiries among the more extensive works

on every branch of the subject. They can be assured that they

will be well repaid by the increased delight they derive from our

fascinating old churches.

J. LITTLEJOHNS

EXPLANATORY REMARKS

Explanatory remarks of the meanings of several items mentioned

in the text are given below:

Medieval Times or Middle Ages. Generally descriptive of

the period from the fall of Rome to the discovery of America,

but, for the purposes of this book, regarded as covering the 10th

to the 16th centuries inclusive.

Mass. The central act of worship of the Roman Catholic

Church performed daily; the climax of the ritual is the offering by

the priest at the altar of Christ’s Body and Blood as intercession for

the souls of the faithful, living and departed.

Host. The elements, bread and wine, consecrated at the altar,

and believed to have been changed thereby into the veritable

Body of Christ.

PYX. The receptacle, suspended over the altar or kept in a

locked aumbry, in which the Host (usually in the form of a consecrated wafer) is reserved for administration to the sick and dying, and for adoration by the congregation.

The Reformation. The great religious revolution of the 16th

century. The Church, more particularly the greater monasteries,

had accumulated much wealth, chiefly in the form of landed estates;

the upper clergy, often appointed by the Secular Authority on

political grounds, were frequently pluralists and absentees; there was

some slackness and self-indulgence, and many superstitious usages

had grown up; payments to the Papacy became burdensome and

the interference of the clerical courts in the lives of the people was

resented; the Reformers objected to the doctrine of transubstantiation (the belief that the bread and wine, when offered at the altar by the priest, were converted into the actual Body and Blood of Christ). Henry VIII, while claiming to be a Roman Catholic in

matters of doctrine, repudiated the authority of the Pope over the

Church in this country and assumed the position of Supreme Head

on earth of the Church of England; he also suppressed the

monasteries and confiscated their wealth. During the reign of his

successor, Edward VI, the Reformers grew in power; they

abolished the Latin Mass and introduced an English Prayer Book;

chantries were dissolved and the churches plundered of much of

the wealth in ornaments, vestments and sacred vessels. Next came

Queen Mary, who restored the Papal authority and the Mass and

ordered the burning of Protestant ‘heretics.’ Queen Elizabeth

reversed Mary’s policy and established the Church of England

substantially as it exists to-day: the final severance from Rome

came in 1570, when she was excommunicated by Pope Pius V.

Towards the end of her reign the Puritan movement, largely inspired by Calvinist teachings, gained ground and was the main

cause of the civil war in the reign of Charles I; it triumphed for

a short time during the Commonwealth, but the people as a whole

soon tired of the rigid Puritanical regime imposed by the Cromwellian soldiery; the Stuarts were restored in 1660, and the Settlement of 1662 removed the Puritan ministers and re-established

the Prayer Book of Elizabeth with certain minor modifications of

a ‘High Church’ character.

Puritans. A body of earnest religious reformers who aimed at

combining a stricter morality with a simpler form of worship;

they objected to the rule of bishops and to the term ‘priest’; and

to the use of set prayers and the wearing of vestments, were

anxious that the ‘Communion table’ should not be regarded as an

altar, and disapproved of church paintings and ornaments as

tending to superstition and idolatry in our churches. They were

responsible for the destruction of many of the artistic treasures that

had survived from the Middle Ages.

Visitors to our churches will find that the order in which the

pages of illustrations in this book are arranged forms the most

convenient way of going round, except that gravestones in the

churchyard could be left until the end of the visit if desired.

In the brief notes attached to each page of illustrations, objects

which are not very common are marked with an asterisk *, while

the words in brackets thus, (S. wall of the chancel), indicate the

part of the church where the object can usually be seen.

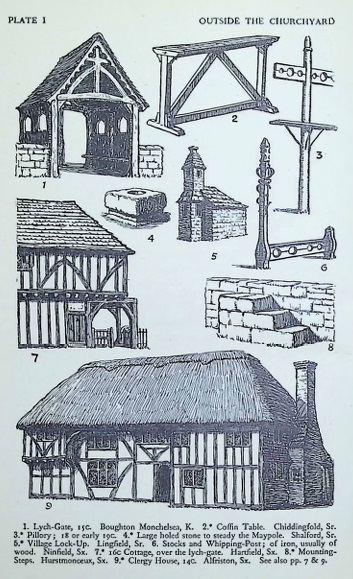

OUTSIDE THE CHURCHYARD

It is often worth while looking around a village for interesting

remains of ancient customs, a few of which are mentioned

below.

Pillory, No. 3. Evildoers were made to stand on the raised

platform with their head and arms through the holes in the

cross-piece while they were exposed to indignities from the

villagers.

Stocks and Whipping-Post, No. 6. The victims sat with

their legs locked in the stocks and received similar treatment to

those on the pillory. Those sentenced to receive lashes with a

whip stood with their hands fastened to the whipping-post and

their clothes stripped from their backs.

Ducking-Stool. A form of chair on wheels attached to a long

pole. Scolds and disorderly women were strapped in the chair

and ducked several times in the village pond. Only a very few of

these stools remain.

Lock-Up, No. 5. Used for confining law-breakers until they

could be brought before the proper authorities.

Maypole, No. 4. The first of May was kept as a festival to

celebrate the return of Spring. The Queen of May was chosen

and crowned with a garland of flowers. There was a procession

to the village green, dancing round the Maypole, and sports.

These celebrations were suppressed by the Puritans, revived after

the Restoration in 1660, and then gradually declined in importance.

Mounting-Steps, No. 8. For those who rode their horses to

church and were not very agile, these steps were helpful on re

mounting.

Clergy House, No. 9. Some of these 14th to 16th century

buildings are fine specimens of the old craftsmen’s skill and artistic

taste. Being near the church, they were convenient for the priest

to get to the many services he had to conduct each day. Only

a few of these are left. There are quite a number of beautiful

successors to these medieval clergy houses in the form of residences

for rectors and vicars.

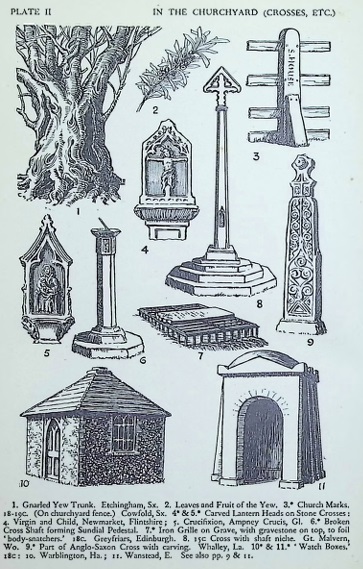

IN THE CHURCHYARD (CROSSES, ETC.)

Tithe Barn. Payments ‘in kind’ to the clergy of corn, fodder,

etc., were stored in these Medieval barns, some of which were

of a great size.

Inn. In the days when pilgrims travelled long distances to do

homage at the shrine of some saint, guest houses or inns were

provided to accommodate them. Many of these inns remain,

bearing religious names, such as ‘The Cross,’ ‘Angel,’ ‘Mitre,’

‘Lamb,’ ‘Bell,’ ‘Star,’ ‘Cross Keys,’ etc. Although they have

been restored and partly rebuilt, many retain their old-world

atmosphere, and with oak beams and doors, quaint staircases,

large open fireplaces, odd nooks and corners, present a picturesque

appearance.

Lych-Gate, or ‘Corpse-Gate,’ Nos. i and 7. Lych was the

old English word for a dead body. At the lych-gate the coffin

was rested on a wooden or stone table, No. 2, while the priest

said part of the burial service. Only rich people were buried in

coffins in Medieval Days; the poor were brought in a parish one,

usually carried on the parish bier (a few of which still remain),

then taken out and wrapped in a sheet for burial direct in the

ground. To give impetus to the wool trade of the country, an

Act was passed in 1678 forbidding anyone, under a penalty of

to be buried unless they were wrapped in a woollen material.

The Act was repealed in 1814. Few lych-gates of a date earlier

than the 17th century remain. Many have been restored or rebuilt.

IN THE CHURCHYARD (CROSSES, ETC.)

In Medieval Times churchyards were busy places. On Feast

Days there were dancing and games, including ‘fives,’ which was

played amongst the buttresses of the church. Fairs were held at

definite times. Travelling merchants set up their stalls and booths

and plied a busy trade. Churchyards were not so full of graves

and gravestones in those days. In some cases the church was

built on the old heathen burial-ground; thus the churchyard

would be older than the church, or even the cross, which may

have been set up before the church was built.

Yew Tree, No. 1. Old yew trees exist in many churchyards.

IN THE CHURCHYARD (CROSSES, ETC.)

They are, in some cases, older than the church. Ancient Britons

were pagans, and it is quite possible that the yew trees are vestiges

of the ‘groves’ in which the pagans worshipped. The trunks

and branches of very old yew trees are twisted and gnarled, but

still stand against the storms that beat upon them. They were

looked upon as the emblem of immortality. Edward I ordered

the planting of yew trees, as, by reason of their close growth,

they formed a protection for the church against high winds and

storms. Twigs and boughs of the tree were used to decorate the

churches at Easter, and were also used as a substitute for the palm

on Palm Sunday.

Crosses, Nos. 4, 5, 6, 8 and 9. A number of crosses were set up

by the missionaries from Rome to remind the people of Christ’s

sacrifice made for them, and used as positions to preach from

before the churches were built. The cross was an important

‘station’ in the Palm Sunday processions and was sometimes used

for public proclamations. Some had a niche in the shaft, No. 8,

for the pyx (a receptacle containing the Host). Anglo-Saxon

crosses were usually enriched with elaborate carving, No. 9, but

few of these remain. Later Medieval crosses were of two types:

lantern, Nos. 4 and 5, and those with arms, No. 8. Both types at

times were enriched with sculptured figures, Nos. 4 and 5.

Church Marks, No. 3. The names of near-by mansions or

farms carved on old churchyard fences indicated that the tenants

were responsible for keeping that part of the fence in a proper

state of repair, and are interesting reminders of the times when

the responsibility for the fabric, etc., of the church devolved on

all parishioners.

Watch Boxes, Nos. 10 and 11. In the 18th and early 19th

centuries, when surgical science was beginning to develop, die

prejudice against the dissection of bodies was so great that medical

students were driven to what was called ‘body-snatching,’ i.e.

removing the bodies of newly buried persons at night. To prevent

this, a small building, called a watch box, was erected in the church

yard, and in this, armed men were on guard at night to foil the

activities of ‘body-snatchers,’ or ‘resurrection men’ as they were

sometimes called. Another form of protection was a heavy iron

grille, No. 7, covering the grave, with the headstone placed on top

of the grille.

IN THE CHURCHYARD (HEADSTONES, ETC.)

The oldest graves are South of the church. People wished to

avoid the shadow of the church falling on their graves, and the

North side was often associated with the Devil. The churchyard

on the South side is often higher than the road outside and the

church door-sill. This is due to the Medieval custom of burying

people on top of others, and so gradually raising the level of the

ground. Few gravestones earlier than the 17th century remain.

Table Tombs, Nos. 1 and 13, followed the form of altar tombs

inside the church, and the tops, raised above the ground, did not

get overgrown with weeds. Provision was made by the wills of

some charitable persons for the distribution of bread and beer to

the poor. The tops of table tombs near the porch were some

times used for this purpose. The 18th and 19th century copies

of these old table tombs, No. 13, were often heavy and clumsy in

appearance.

Headstones, Nos. 2 to 6, 9 and 10, were counterparts in the

churchyard of the wall tablets within the church. Their purpose

was to display inscriptions giving details of the deceased persons.

Numerous examples, dating from the 17th century onwards, are

to be found in old churchyards, the earliest ones being low and

very thick. Small footstones preceded the use of headstones.

Some graves possess a ‘body,’ a long flat or rounded stone placed

horizontally between the vertical stones at the head and foot.

Many headstones were carved with classical emblems of mortality:

skull, crossbones, hour-glass (‘sands of time run out fast’), scythe

(‘death the reaper’), etc. Inverted torches, No. 3, are symbolical

of death, darkness and night, while uplifted torches signify life,

light and day. A serpent biting its tail and forming a circle, No. 4,

signifies Eternity. This example encloses the ‘All-seeing Eye’ of

God. The book and pen of the ‘Recording Angel’ are shown

by No. 6.

Bed-Head, No. 11. These are cheap wooden substitutes for

stone and are common in some counties. Being constructed of

wood, many have become dilapidated, but quite a considerable

number remain.

Iron, No. 12. In bygone days the smelting of iron was carried

on in Kent, Surrey and Sussex. In these counties iron was used

TOWERS AND SPIRES

for some gravestones in the church and churchyard, while in some

districts slate, No. 2, was utilised for the purpose.

Recessed Grave, No. 7. In very thick walls a recess was

constructed and formed a covering for the effigy which sometimes

rested in it.

Many modern headstones are made from white marble, a foreign

material which does not harmonise at all with the mellowed stone

of the old church.

Some epitaphs on headstones are quite amusing, while others

record tragedies. Three examples are given below.

To a pirate:

Pray then ye learned Clergy, show

Where can this brute Tom Goldsmith go?

Whose life was one continued evil,

Striving to cheat God, man and Devil.

To a soldier:

Here sleeps in peace a Hampshire Grenadier,

Who caught his death by drinking cold small beer,

Soldiers, be wise from his untimely fall,

And when you’re hot, drink Strong or none at all.

To a murdered sailor:

When pitying eyes to see my Grave shall come,

And with a generous Tear bedew my Tomb,

Here shall they read my melancholy Fate,

With Murder and Barbarity complete,

In perfect Health and in Flower of Age,

I fell a victim to three Ruffians’ Rage.

On bended Knees, I mercy strove to obtain,

Their thirst of Blood made all entreaties vain,

No dear Relation or still dearer Friend,

Weeps my hard lot or miserable end,

Yet o’er my Sad Remains (my name unknown),

A generous Public have inscribed this Stone.

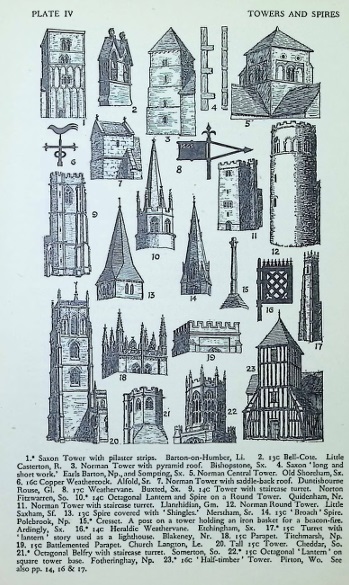

TOWERS AND SPIRES

Towers appear like giant sentinels watching over the people.

Their primary use is to house bells, to call people to worship,

and spread tidings, joyful and sad. Bells are heavy, and so towers

are strongly built. In Medieval Times towers were useful as a

defence against marauding bands, and were guides for travellers

by land and sea. At night a beacon-fire, No. 15, or lamps in the

TOWERS AND SPIRES

windows of a ‘lantern’ upper story, Nos. 17 and 22, were used.

Some small churches have no tower, bells being housed in an

opening at the apex of the Western gable or a bell-cote, No. 2,

above it.

Position. This varies according to convenience. The majority

being at the West end, some are central, Nos. 5 and 7, others are

attached to a transept or the nave, sometimes with their lower

story as a porch. A few are detached.

Shape. The majority are square, Nos. 1, 3, 5, 9, 11, 17 and 20,

a small number rectangular, some, in districts devoid of large

stones necessary for the angles of square towers, are round, No. 12,

and a few with the upper story octagonal on a square or round

base, Nos. 10 and 21. Belfry windows are really ‘sound-holes,’

filled with louvres allowing the notes of the bells to radiate. Access

to the upper,stories is by an interior ladder (see Plate XXIV), or

a staircase turret, Nos. 9, 11 and 21. An effect of stability was

obtained by the width of the tower receding to the top, either by

‘battering,’ No. 11, stepped upper stories, No. 3, or buttresses

projecting less stage by stage, Nos. 9, 17 and 20.

Roof. Many early towers lack their original roof. Saxon roofs

were probably similar to Norman, a form of low pyramid, Nos. 3

and 5. A few 12th and 13th century ones had a ‘saddle-back’

roof, No. 7. In the 13th century the pyramid form became taller,

developing into the spire, No. 13, covered with oak ‘shingles,’ lead

or copper. ‘Broach’ spires, No. 14, were common in the 13th

century; later, in the 14th century, spires rose behind parapets,

No. 10. Not many spires were built in the 15th century, most

roofs being flat, behind parapets, Nos. 18, 19 and 20. Copper

weathercocks, No. 6, symbolic of vigilance, and weathervanes,

Nos. 8 and 16, decorated with coat-of-arms, emblems of saints,

etc., are interesting remains of old craftsmen’s work.

There is space only for a few brief indications of styles. Windows,

doors, buttresses and decorative details are characteristic of their

periods (see Plates V, VI and VII), but some early towers have

been altered and added to in later times.

Saxon towers, No. 1, with double belfry windows, ‘long and

short work,’ No. 4, and pilaster strips as decoration, No. 1, are

taller than the low massive Norman* ones, which seldom rise much

above the church roof. Corbel tables (see Plate V) and staircase

EXTERIOR WALLS OF CHURCH (BUTTRESSES, ETC.)

turrets, No. 11, are found on Norman towers. Some 13th century

towers are low, others more lofty; belfry windows are larger and

recessed. In the 14th century belfry windows are the central

feature and richer decorative details were used. The 15th century

was a period of magnificence in tower building, Nos. 18 and 20;

some are very tall, often, if added to an earlier church, dwarfing

the building; windows are large and some parapets richly decorated,

Nos. 18 and 20. In forest districts in the 16th century a few towers

were built in the ‘half-timber’ style, No. 23, with oak framework

filled in with a form of cement.

EXTERIOR WALLS OF CHURCH (BUTTRESSES, ETC.)

Buttress, Nos. 16 to 21. The weight of a roof tends to thrust

the walls outwards, therefore it is necessary to construct walls

that are very thick, or strengthen them with built-on projections,

called buttresses. These are usually placed at points where the

roof trusses (see Plate XXII) are fixed. Buttresses give support

in proportion to their weight, so the thinner the wall, the heavier

the buttresses should be.

Many Norman walls are at least three feet in thickness, and

their buttresses, No. 16, which are really pilasters with little projection, just tend to stiffen the walls and serve a decorative purpose

in breaking the monotony of a large plain wall surface. In the

13th to 15th centuries walls became thinner, and being weakened

by larger window openings, the projection of the buttresses was

gradually increased, Nos. 17 to 20. Some have pinnacles at the

top, No. 18, which add to the weight, tend to throw off the

rain, and serve to beautify the skyline of the building. Some

buttresses have a niche, No. 19, to house the statue of a saint, and

in the later part of the 15th century carved panelling was used

as decoration, No. 21. When the nave walls were raised to take

the clerestory windows (see page 21), they were occasionally

strengthened by an arched-shape stone construction between this

wall and the buttress of the aisle wall, known as a flying buttress,

No. 13.

Corbel Table, Gargoyles, and Parapets, Nos. 1 to 4, 7 to

12 and 15. To throw the rain from the roofs clear of the walls,

EXTERIOR WALLS OF CHURCH (WINDOWS, ETC.)

in early times projecting roofs were used, these being carried on

corbel tables, No. i, a form of cornice supported by corbels,

Nos. 2, 3 and 4. Many of these corbels were carved with quaint

heads and figures. Later, gutters, with gargoyles, a kind of stone

water-spout, Nos. 10 to 12 and 15, were used. The common

belief was that dragons and demons infested the church. Carved

forms of these were used for gargoyles, so that they were thus

made to protect the church they wished to destroy. Others

represented human vices as a warning to all who entered the

church to leave their evil passions outside. In the 14th and 15th

centuries some walls were elevated above the gutters in the form

of parapets, often like a battlement with carved details, Nos. 7 to 9.

‘Mass’ or ‘Scratch’ Dials, Nos. 5 and 6. A form of sundial used

to mark the times of the church services before mechanical clocks

began to be more commonly used in the 15th century. In Medieval

Times the walls of churches were coated with a form of cement

and limewashed both inside and outside, and mass dials were

usually painted in the scratched lines. A metal rod, called a gnomon,

projected from the central hole to cast the shadow.

In the 18th century, sundials, No. 14, were used to mark the

hours of the day.

Consecration Crosses, Nos. 22 and 23. For the dedication

of the church twelve crosses were carved or painted, or metal ones

fixed, outside and inside the walls of the church. These were

anointed with holy oil by the bishop. There may be, above or

below the crosses, a hole for the bracket for the candle used at the

ceremony. Candles were also lighted on the anniversary of

consecration day. These crosses were about seven to eight feet

above-ground to prevent passers-by brushing against them. The

bishop used a short ladder to reach them.

EXTERIOR WALLS OF CHURCH (WINDOWS, ETC.)

Windows. Saxon, Norman and early 13th century windows,

Nos. 1 to 6, were small. Glass being expensive, they were unglazed or filled with horn, parchment or oiled silk to exclude the

wind and rain. Windows placed high up in the wall tended to

reduce discomfort from draughts. These 12th and 13th century

EXTERIOR WALLS OF CHURCH (WINDOWS, ETC.)

windows were splayed inside, Nos. 4 and 6, to admit more light,

but, as they were small and few in number, churches were gloomy.

In the 13th century, to secure more light, two or more ‘Lancet’

windows, with circular openings over them, No. 9, were placed

close together under a dripstone (an arched moulding which prevented rain running down the wall into the window); this arrangement was known as Plate Tracery and was the origin of—

Bar Tracery, Nos. 7, 8, 10, 11, 13 to 15. From the 13th to

the 16th centuries, as builders gained experience and glass became

cheaper, windows gradually increased in size, until some 15th

and 16th century churches had the appearance of a huge expanse

of glass held together by narrow strips of stone. Windows were

divided into divisions, called ‘lights,’ by ‘mullions’ (vertical bars

of stone), which developed at the top into curved bars forming

various shapes known as tracery. In the 15th and 16th centuries

large windows had ‘ transoms ’ (horizontal bars), No. 13, for additional strength. Besides being decorative, tracery acts as a

support to the window arch, and enables the glass to withstand

wind pressure. It gave Medieval craftsmen opportunities of filling

windows with beautiful stained-glass pictures (see page 70).

Tracery first consisted of geometrical shapes, No. 7; then, later

in the 14th century, flowing lines known as curvilinear tracery,

No. 8, were used.

Window Arches. Saxon and Norman were semi-circular and

13th century ones very pointed. As windows were built wider,

arches became less acute, until, in the 15th century, four-centred

ones, No. 14, were used. Some 14th century arches were ogee

shape, No. 15, while segmental arches, No. 10, and square heads,

No. 11, were used in the 14th to 16th centuries. Occasionally,

circular windows, No. 12, dating from Norman times onward can

be found.

Clerestory Windows. When a church was constructed with

aisles, or had them built on later, nave walls were raised above

the aisle roofs and windows inserted to add more light to the nave,

though some appear rather small for this purpose.

‘Low-Side’ Window, No. 16, was lower than the others, placed

at the West end of the chancel and usually on the South side, and,

in Medieval Times, had shutters to open and close. The purpose

of this window has aroused much controversy, but most authorities

PORCHES, ETC.

agree that the ‘Sanctus bell’ was rung there to remind those in

and outside the church of the solemn moment of the Mass when

the ‘Host’ was elevated at the altar.

Sanctus Bell-Cote, No. 17. Built over the West end of the

chancel on some churches to house the ‘Sanctus bell.’

Priests’ Door, No. 16. The chancel was the peculiar responsibility of the rector, and he had his own entrance. This was useful

at nights when he had to obtain the necessary articles if called to

visit die sick and dying.

Anchorite’s Cell, No. 18. Anchorites and anchoresses were

persons desirous of living pious lives. Each was conducted in a

procession to the cell, the door of which was blocked up and

sealed, die occupant spending the rest of his or her life in it. A

small window admitted light, and through this food was passed;

another window gave a view of the altar. Some cells had a fire

place. Few remain to-day.

PORCHES, ETC.

Porches, Nos. 5 and 7. Most churches have one on the South

side, some on the North if the old Manor House lay on that side.

There were few porches in die 12th and 13th centuries, but in the

14th century they began to be regarded as a necessity. Many old

ones were allowed to deteriorate and were replaced by new ones.

The porch was most important in Medieval Times. There penitents received absolution before entering the church; those

breaking vows did penance, and those breaking the marriage vows

stood, wrapped in a white sheet; women knelt to be ‘churched’

after the birth of their child, and baptismal services commenced;

marriage banns were called, part of the marriage service was held,

and the ring placed on the finger; civil business was carried out,

executors of wills made payment of legacies, coroners sometimes

held their courts, and public notices were exhibited. The porch

was one of the ‘stations’ during church processions. It protected

the church door against inclement weather. Stone porches were

built in all periods, while oak-framed ones on a stone base, No. 7,

were used in the 14th and 15th centuries. Most porches had a

PORCHES, ETC. “

niche, No. i, for a figure of the patron saint, while many seats

were of stone, No. 8, high and low, for adults and children. Some

porches have a room over them, No. 5, used for various purposes.

It provided a safe place for books and documents of the church

and parish, for the library that some churches possessed, and a

depository for wills. Some of these rooms were used by Chantry

Priests to sleep in to be ready to celebrate early Mass for travellers.

Frequently one of the conditions of a Chantry bequest was that

the priest should teach boys Latin, the language used for

church services; the room being used for this earliest form of

school. The responsibility for raising the local quota for Militia

service rested on the parish authorities, and armour was stored in

the room.

Stoups, Nos. 2 and 3. Recessed basins, outside or sometimes

just inside the church door, containing ‘holy water,’ consecrated

every Sunday. All entering the church dipped their finger in and

made the sign of the cross on their forehead and breast to remind

them of their baptismal vows, and the need of cleansing from sin,

and the frailty of human life, ‘unstable as water.’

Graffiti, Nos. 6 and 10. Interesting ancient markings of

various shapes cut in parts of the stonework of many churches,

the purpose of which cannot be definitely stated. It is thought

that some denote the registering of a vow, or were signs cut on

the eve of a venture, or, the crosses particularly, cut by pilgrims

pausing at the church on their journey to some shrine. These

crosses are known as ‘votive crosses’ or ‘pilgrim marks.’ Some

may have been cut to scare evil spirits away. The marks, No. 10,

may have been cut by stone-masons, proud of their work, much

as an artist puts his signature on his picture, or merely cut for the

convenience of reckoning piecework, etc.

Cresset Stone, No. 9. A stone with cup-like hollows filled

with oil and floating wicks to give light for those performing the

night duties in the church. Few of these remain.

Chain, No. 4. For drovers to tie up their cattle to prevent them

straying while they themselves attended Mass.

DOORS

There is the actual wooden door, also the opening and surrounding stone mouldings, etc., generally referred to as the door

way. Most early churches had South and North doors, some a

West one as well. The North door was known as the ‘Devil’s

Door,’ and was left open at baptismal services so that the evil

spirits supposed to be in the child could, when it was christened,

pass from the child through the doorway. This door was also

used for the procession, an important ceremony in Medieval

services. Those taking part passed through it down the centre

of the churchyard, round the East end of the church, and in again

by the South door. In some churchyards can still be seen the

path used for processions. The North door is often blocked up

now, due probably to the dislike of draughts.

Saxon doors were plain, but from Norman times onwards

doors were decorated to add beauty to them, probably with this

saying of Christ’s in mind, ‘I am the door: by me if any man

enter in, he shall be saved.’ Norman doors and doorways, Nos. 8,

10 and 16, were often the most elaborate feature of small churches;

some had a carved panel under the arch, No. 16, known as a

tympanum. In Saxon times, and 12th and early 13th centuries,

doors were strongly built. These proved useful if the church

had to resist attacks by robbers or invaders. They were constructed of thick oak boards, showing tool marks, placed vertically

outside and horizontally inside, Nos. 1 and 2, and fastened together

by long wrought-iron nails with ornamental heads, No. 3, that

were driven right through and clenched over on the inside.

Early doors often provided the sole surviving examples of the

work of the smith, that most important of Medieval craftsmen.

His work, consisting of wrought-iron hinges, locks, handles and

knockers, Nos. 5, 7 to 10 and 15, not only added beauty to the

door but greatly increased its strength. A part of Norman hinges,

Nos. 8 and 10, in the form of the letter C, was supposed to refer

to St. Clement, the patron saint of smiths. The churches afforded

temporary sanctuary for persons fleeing from processes of the law,

who no doubt used the knockers on the doors to gain entrance.

This privilege was abolished in the 17th century. In the 13th

century the ironwork was very elaborate, the outside face of the

doors being covered with scroll-work, No. 7.

PLANS

Later, in the 14th and 15th centuries, the craft of the carpenter

replaced that of the smith in door decoration. At first simple

mouldings were used to cover the joints, No. 6, then decorative

forms were copied from the tracery of the windows. These tracery

forms were first carved in the solid woodwork of the door, but

later were cut out of wooden boards and fixed to the door with

glue and nails, No. 14. Hinges and locks were smaller and plainer.

Most 13th and 14th century doorways were plain, but some 14th

century ones had an ogee-shaped ‘dripstone’ or ‘hood moulding’

as it is sometimes called, with crockets and finial carved for decoration, No. 13. 14th century dripstones were often finished with

carved heads of kings and queens, or knights and ladies. Many

15th century dripstones were square, having a four-centred arch

under, with the spandrils filled with shields, heraldry, tracery or

foliage, No. 4. Some churches had double doors, suggesting the

two natures of Christ, human and Divine. Large churches some

times had three doors, signifying the Holy Trinity.

PLANS

Church plans vary, but all can be traced back to one of three

types: (A) Nave and sanctuary, No. 1; (B) Nave, chancel and

sanctuary, No. 3, and No. 4 (chancel under the tower); (C) Cruciform with nave, chancel, transepts and central tower. Type (B)

did not continue as a permanent form.

From the 7th to the 16th centuries, churches were primarily

shelters for altars. People attended church to see and hear priests

celebrate Mass. Aisles were added to accommodate more altars,

larger congregations, and provide paths for processions; chancels

lengthened for increased ritual; porches, sacristies, towers and

chantry chapels built on, until often little remained of the original

church. Nos. 6 to 10 show additions to type (A), and Nos. 11

and 12 those to type (C). Some central towers collapsed and were

rebuilt at the West end, No. 12. Round churches, No. 6 A,

founded and endowed by the Hospitallers, or the Templars, were

built in imitation of the Rotunda of the Holy Sepulchre at Jerusalem.

Only four remain.

FONTS AND COVERS

Sanctuary. That part of the church occupied by the high altar.

Chancel. The Eastern part of the church, separated from

the nave by a screen (see Plate XI), and used by the deacons and

servers assisting the priest in the services.

Sacristy or Vestry. A room, with the entrance inside the

church, for keeping sacred vessels, vestments and other valuables

in. The priest used it to deck himself for the services.

Chantry. A Medieval ecclesiastical endowment for maintaining

priests to chant Masses for the soul of the testator or others named

by him. This act was considered to be the surest way to secure

the soul’s welfare. The testator, or members of merchants’ and

craftmen’s guilds, often provided a chapel for the purpose, con

taining the tomb of the testator.

FONTS AND COVERS

Fonts, Nos. 1 to 4, 7 to 11 and 14. These are generally situated

near the main entrance at the West end of the church. In Medieval

Times the baptismal service began in the porch, or outside the

door if the church did not possess a porch, and finished at the font.

Few authentic Saxon fonts remain. In many cases wooden

tubs were used. There are a large number of Norman fonts.

Being constructed of large stones, and bearing no weight, and

because of the sanctity attached to the rites associated with them,

they were preserved when the Norman church was altered, and

rebuilt. The design of the font was suggested by the prevailing

type of architecture. Most fonts were made of stone, some of

lead, and in the 13th century a number were of marble. These

usually had but little carving, the polished marble itself adding

richness to the effect.

Early fonts were tub-shaped, large and deeply hollowed. In

Saxon times adults stood in the font and water was poured over

them. Later, when the baptised were mostly children, these were

immersed, and so the font was raised on a low stand for convenience; when, later still, sprinkling became the custom, the

bowls were made smaller and raised still higher on pillars, Nos. 8

FONTS AND COVERS

and 11, or pedestals, Nos. 9 and 14. In the 15th century the

pedestal sometimes stood on a flight of steps. These different

methods of baptising account for the lack of unified design, and

for the fact that some bowls are of an earlier date than the base

they stand on. There were stereotyped designs in all periods,

but the exceptional ones are usually more interesting, Nos. 1, 2,

3 and 10. Weird beasts and figures carved on some Norman

fonts probably symbolises the escape of the soul from evil through

baptism. The large variety of design in fonts adds much to the

interest of our old churches.

The illustrations show a few of the different forms that have

survived. The comers of square fonts, No. 3, were, in Medieval

Times, for the candles and vessels of oil and salt used at the baptismal ceremony. Lead fonts, No. 2, were made by stamping

wooden patterns in a sand mould, pouring the molten metal in,

and afterwards bending it round and soldering. Most 14th and

15th century fonts were octagonal in form, many being of graceful

proportions, while some were elaborately carved with designs

representing the seven cardinal virtues or seven sacraments. The

seven virtues are Faith, Hope, Charity (called the Holy Virtues),

Prudence, Justice, Fortitude and Temperance. The seven sacraments are Baptism, Confirmation, the Eucharist (Mass), Penance,

Ordination, Matrimony and Extreme Unction. Other favourite

subjects were symbolic representations of the four Evangelists

(see Plate XXVI) and heraldic devices.

Covers, Nos. 6, 12 and 13. Very early fonts did not have

covers. In the 13th century the Archbishop ordered that covers,

which were flat, should be locked. The water being consecrated,

people, believing it contained some magic power, tried to steal it

for superstitious purposes. On some fonts can be seen the staple,

or place where the staple was, which was used in fastening the

lid, Nos. 5 and 7. Some covers, known as rim buffets, No. 12,

are permanently fixed to the top of the font, and possess a door

which could be locked, while others are in the form of floor buffets

which enclose the whole font completely. Very large elaborately

carved covers, No. 13, belong to the 15th century and require a

pulley with rope or chain to raise them.

CHANCEL SCREENS

Screens are used in churches for various purposes: to enclose

the choir, to separate chapels from the chancel or nave, in which

case the screen is known as a parclose, and to protect tombs.

Chancel Screen, No. 4. In Medieval Times the chancel was

reserved for the priest and his assistants, and the nave for the

congregation, as the screen, with its locked doors, was used to

keep the people, and dogs (who were the scavengers of those days),

from the chancel.

Early screens were of stone, but in the late 14th and 15th

centuries oak was used. Over the screen was the Rood beam on

which was fixed the Rood (an image of Christ on the Cross with

figures of the Virgin Mary and St. John). The Rood was the dominating feature of the Medieval church. The figures were destroyed

at the Reformation, but No. 4 gives some idea of their appearance.

The Rood beam sometimes became embodied in a wooden

screen, and the top of the screen was in the form of a loft, approached

by a staircase and door in the wall at the side, No. 4. The loft

was often used for a small organ, for soloists of the choir, to read

the Gospel from, to facilitate the decking of the Rood with foliage,

and for the lighting of candles on the upper part of the screen on

festival days. The ceiling over the screen was richly decorated

to show the sanctity of the Rood. A lamp in front of the Rood

was always alight, and during Lent the Rood was covered with a

veil. In some churches there was a window, high up on the South

side, to light the Rood.

Highly skilled wood-workers of the 15th century put their

best work into these screens. They were enriched with beautiful

carving, as those screens that still remain show. The screens,

like all other wood and stone work, were coloured and gilded,

the lower panels of some being painted with pictures of saints.

Traces of colour can still be seen in a few churches. Unfortunately,

the mistaken zeal of the 16th century Reformers destroyed most

of these beautiful screens, and later, Parliamentary .troops made

havoc of much of the Medieval craftsmen’s lovely work in our

churches. A number of fine old screens remain in East Anglian

and Devon churches. If the screen is missing, the staircase, door

or corbels for the Rood beam may sometimes be seen. In Medieval

IN THE CHANCEL (TABLES, CHAIRS, ETC.)

Days, miracle plays, the Passion play at Easter and Nativity play

at Christmas were performed in front of the chancel screen.

‘ Squints ’ or ‘ Hagioscopes,’ Nos. i, 2 and 3. In some churches,

cut at an angle through the wall at the side of the chancel arch, is

an opening, Nos. 1 to 3. This gave people in the aisles a view

of the high altar. Then, if a priest was officiating at an altar in

the aisle, he could use the squint to view the high altar and thus

synchronise the two services.

IN THE CHANCEL (TABLES, CHAIRS, ETC.)

Altar, No. i. The altar at the East end of the chancel was

known as the high altar. The ceiling over it was often richly

decorated. Prior to the Reformation most altars were of stone,

with five crosses (one in each comer and one in the middle),

signifying the five wounds of Christ. The few remaining ones

now in use are mostly found in Chantry chapels. Some were used

in floors and walls during rebuilding after the Reformation. To

keep the draughts from the candles on the altar, curtains, often

beautifully embroidered, hung North and South of the altar.

Some stone altars contained the bones of saints. In Medieval

Times, during Lent, a veil was hung in front of the altar, suspended from a cord attached to staples about eight feet from

ground on the North and South walls. Some of these staples

still remain.

Reredos, Nos. 2, 3, 11 and 13. The East window, with

brackets and niches containing figures of saints on either side of

the altar, and the space between the top of the altar and window

sill formed the reredos; this space being decorated with canopied

niches of stone or alabaster containing carved figures, or some

times panelled with paintings. The favourite subjects were the

twelve Apostles, holding their appropriate emblems, and scenes

from the Passion. Few churches retain the old reredos, most

having embroidered hangings or wooden panels instead. Some

churches in the 17th and 18th centuries used panels containing

the Ten Commandments, the Lord’s Prayer and the Creed. These

panels, with some modern reredos, are so large that they cover

IN THE CHANCEL (SEDILIA, PISCINA, ETC.)

part of the East window and detract from the beauty of it. A

reredos was used at the back of altars in the chapels and aisles.

Pyx Pulley. Usually housed in a socket in the ceiling, No. 4,

and used to raise and lower the pyx.

Communion Table, Nos. 10 and 14. After the Reformation,

a table replaced the stone altars, and was moved to the middle of

the chancel for the Communion service while the congregation

sat or stood round it. Some strong-minded Puritans placed the

table in the nave. Elizabethan tables, No. 14, were given a rich

decorative appearance by wood-carvers, but Jacobean ones are

plainer. The beautiful colour of the old oak is worth noting.

Credence, No. 5. A small stone table on which stood the

wafers and wine before they were consecrated at the altar.

Brackets, Nos. 6, 7 and 8. Carved stone brackets on which,

in Medieval Times, carved images of the Virgin Mary or saints

used to stand. These figures were draped with veils during Lent.

Oven, No. 12. Ovens in churches were used to bake the wafers

for Mass, and to heat the charcoal for incense-burners.

Chairs, Nos. 9 and 15. A special chair on the North side of

the chancel which is used for the bishop officiating at the Confirmation service and other functions. Some of these chairs are

excellent examples of the woodwork and carving of old craftsmen.

IN THE CHANCEL (SEDILIA, PISCINA, ETC.)

Sedilia, Nos. i and 6. This was usually the most ornate

feature of the chancel. In Medieval Times, during Mass, the

priest was the celebrant, the deacon read the Gospel and the sub

deacon read the Epistle. They were seated in the sedilia while

the Creed and Gloria were being sung, giving them a period of

rest during the long ceremony. The seats were often of three

different heights; the priest sat on the highest one, nearest the

altar. Later, when Chantry endowments provided some churches

with several clergy in full orders, seats were on one level. Some

sedilias have two seats, others three, while a few have four, the

extra one being for the clerk. Note No. 6, how the chancel floor

has been raised in more recent times, the sedilias not being used now.

IN THE CHANCEL (SEDILIA, PISCINA, ETC.)

Piscina, Nos. 2, 3 and 6. A basin, with a drain leading to

the consecrated ground of the churchyard, for the priest to wash

his hands before Mass and to wash the vessels after the ceremony.

Some have a shelf, No. 3, called a credence. The sacred vessels

used at Mass stood on this. A piscina may be seen in the aisle

or in other parts of the church, denoting that an altar stood there

at some time.

Aumbry, No. 4. A small cupboard for storing the vessels

containing the holy oils used at the baptismal service and the

oil for anointing the sick when they were very ill. These oils

were blessed and prepared in a cathedral by the bishop on Maundy

Thursday. Most wooden doors of aumbries have disappeared,

but the slots for the hinges and the lock can often be seen.

Tiles, No. 5. Not many old encaustic tiles, used for the

floor of the chancel, remain. Many floors have been raised since

Medieval Days. Tiles were made of a red clay, a pattern being

stamped in by a wooden die while the clay was still wet, then

filled in with a white clay, and yellow glaze put over the tile and

fired in a furnace. Some tiles have very interesting and curious

designs.

Easter Sepulchre, No. 7. A recess in the North wall of the

chancel, or a canopied tomb used for the purpose (usually carrying

out a request in the will of the deceased). On Good Friday, in

Medieval Days, the Host and altar cross were placed in the sepulchre

and watched day and night until they were removed, with high

festival, to the altar early on Easter Sunday. This procedure

signified the burial and resurrection of Christ from the tomb.

Altar Rails, Nos. 8, 9 and 10. These were erected in the late

16th century, and nearly all churches had them by the end of the

17th century. Archbishop Laud was shocked at the irreverent

attitude of people when the Communion table was placed in the

middle of the chancel (see page 36). He gradually influenced

church officials to move the tables to the position of the old stone

altars (see page 34) at the East wall of the chancel, and to erect

altar rails for people to kneel at during the Communion service.

These rails also served to keep dogs from defiling the tables.

STALLS, PULPITS, LECTERNS

Choir Stalls, No. 7. Some choir stalls of the 15th century,

that age of wonderful woodwork in our churches, still remain,

with their fine carving giving additional beauty to the chancel.

In Medieval Times, priests, clerks and monks had to stand during

long services; the sloping tops of the stalls were useful to rest

their arms on and thus give them support.

‘Elbows,’ Nos. 2 to 5. The carved projection on the ends of

the stalls, often adorned with quaint and picturesque carved figures,

birds or animals.

‘Misericords,’ Nos. 6, 8, 9 and 15. Some choir stalls have

small hinged seats (somewhat like to the tip-up seats in theatres),

with brackets underneath usually carved with quaint figures,

hunting and farm scenes, and incidents of everyday life. The

wood-carvers were evidently free to give full play to their imagination, for the results are often most amusing. The small

seats were used as a rest for the aged and infirm during long

services.

Pulpits, Nos. 1, 16 and 18. Sermons were first given from

before the altar, then from the West end of the chancel, and

sometimes, it is thought, from Rood lofts, until pulpits were used.

Most early pulpits were of oak, and very small, as though the

priests were not nearly so big as those in more recent times.

Preaching was general in the 15th century. In 1603 church

wardens were ordered to provide pulpits in all churches. Some

old ones still remain. Jacobean pulpits, No. 1, with a sounding

board over to help carry the preacher’s voice to the far end of

the church, were often richly decorated with carving. In the

17th and 18th centuries, when galleries to accommodate larger

congregations were erected, and enclosed pews with high backs

used, the ‘three-decker,’ No. 18, was constructed. The clerk

occupied the lowest part, the next was for the reader of the

Scriptures, and the upper part for the preacher. These pulpits are

not very beautiful, and few remain.

Chained Bible, No. 10. In 1536 the clergy were enjoined by

Royal authority to place a Latin and an English Bible in the choir

of every church, where they could be freely read by the people.

These were chained to the desk to prevent loss by theft.

SEPULCHRAL MONUMENTS (COFFIN COVERS, ETC.)

Lecterns, Nos. ii and 12. These are now used to hold the

Bible from which the lessons are read. In pre-Reformation days

they stood in the chancel to hold the service book, or the chanter

for the conductors of choirs singing at Divine Office and Mass.

A few wooden choir lecterns have desks at two levels for standing

or kneeling. Wooden lecterns were usually of a desk form, No. 11,

and many brass ones had an eagle, with dragons at the foot, No. 12,

symbolising the Gospel carried on wings to the four corners of

the earth, and the dragons as evil powers conquered by the Word

of God. Twenty wooden and forty brass Medieval lecterns remain

in Britain.

Hour-Glass Stands, Nos. 13, 14 and 17. Hour-glasses were

introduced in the 16th century and became usual in the 17th

century. One hundred and twenty of these fine wrought-iron

stands remain. In pre-Reformation days hour-glasses were used

to mark the time of meditations or the Scripture readings of private

worshippers, and later, to time sermons. Some hour-glasses re

corded hours and parts of hours. Tong-winded’ preachers used

to turn the glass upside down when the sand ran down, and so

continued the sermon for another spell.

SEPULCHRAL MONUMENTS (COFFIN COVERS, ETC.)

Stone Coffin, No. 9. In the 12th and 13th centuries stone

coffins were in general use for those of eminence or wealth, and

some were buried in the floor of the church, with the lids forming

part of the pavement.

Coffin Covers, Nos. i to 4. Belonging to the 12th and 13th

centuries, some of these were used as flat sepulchral slabs, others

as actual coffin lids. While some of these slabs are found in the

churches as monuments, they may not mark the actual burial

places, as the bodies may have been buried in the churchyard.

The favourite ornamentation of early ones was the cross and

circle, without lettering. Some were carved, No. 1, others incised,

Nos. 2 and 3. Later, the cross was shown on steps, No. 3, called

a ‘calvary.’ On some, on each side of the shaft of the cross, were

symbols to indicate the profession or occupation of the deceased,

No. 2; swords, shields and other weapons were the symbols for

SEPULCHRAL MONUMENTS (COFFIN COVERS, ETC.)

men-at-arms—bows, arrows, axe and horn for foresters—pastoral

staff and chalice for ecclesiastics—shears, gloves, fish, pincers,

bell, etc., for various tradesmen, while keys indicated that the

person held some official post. Later, these slabs were incised

with a figure representing the deceased; next, the carved semi

effigial figure was used, No. 4, developing later still into the complete effigy carved flat and in low relief. Prior to a.d. 1275,

these slabs were smaller at the bottom end than at the top, Nos. 1

to 4, but afterwards were made the same width at both ends.

When a church had additions built on to it, the slabs were often

taken up and used in the rebuilding. Those remaining in the

floor of the church are mainly found in Derbyshire and Yorkshire.

Iron Slabs, Nos. 5 and 6. These are found chiefly in Sussex,

where iron-smelting was carried on in bygone days. Some slabs

consist of a raised cross, No. 5, without lettering, while others had

a coat-of-arms and an inscription, No. 6. These slabs usually form

part of the floor of the church.

Brasses, Nos. 8 and 10. These consist of thin pieces of metal

(a mixture of copper and zinc), let flush into the stone. The

metal was engraved, and the incised lines filled in with a black

substance, while on some coloured enamels were used. They

came in during the 13th century and continued until the 17th

century, the chief centre of manufacture being London. They

form a most complete history of armour and costume. The early

brasses were used by the wealthy people who could afford to pay

for good work, but later there were cheap substitutes used by the

new middle classes. The engraving deteriorated after the Black

Death, a.d. 1349-50, and figures were made smaller. The finest

collection of brasses is at Cobham, in the county of Kent. After

the Reformation, some of the metal was stolen for other uses.

In many churches can be seen the recess in the stone monuments

from which the metal has been taken. There are about five hundred

brasses still remaining in England.

Ledger Stone, No. 7. In the 17th and early 18th centuries,

when the art of making brasses declined, a School of heraldic

sculptors arose. They carved massive floor slabs of a hard bluish

grey stone. The carving was low in relief, so that these stones,

let into the floor of the church, would not impede those walking

about. The decoration of these slabs usually consists of a coat

of-arms at the top with an inscription under it.

SEPULCHRAL MONUMENTS (EFFIGIES, ETC.)

Monuments erected to the memory of the departed are common

in our churches. Many 13th to 15th century tombs are splendid

examples of the Medieval craftsmen’s work in marble, stone,

wood, alabaster and bronze, adding beauty and richness to our

churches. These monuments, like all Medieval church stone and

wood work, were richly coloured and gilded, but in Puritan times

were whitewashed, and later scraped, so that only traces of colour

remain on a few. Some tombs have beautifully carved canopies

over them. Heraldry, an artistic form of decoration, identifying

persons, and marriages between families, was used from the time

of Edward I onwards.

Effigies, Nos. i and 3. Many tombs, shaped like a huge box,

and known as table or altar tombs, have effigies lying on top.

Carved figures representing Christ, the Virgin Mary, saints and

martyrs were destroyed at the Reformation, but effigies remain to

display the fine work of some Medieval sculptors. These figures,

usually life-size, while representing the deceased person, are not

necessarily portraits—in fact, most effigies portray the person in

the prime of life. When other materials were difficult to obtain,

oak was used; about ninety of these remain. Prior to the Reformation, the effigies were shown in a reverent attitude, with hands

folded in prayer, No. 1, but in the 17th century lolling on the

elbow, No. 3, and other irreverent attitudes were used. In the

16th century the kneeling position, No. 14, was popular. Children

kneeling denote submission to their parents. Renaissance ornament then began to replace Gothic details. Effigies, with brasses

(see Plate XV), are valuable aids for the study of Medieval armour

and costume.

The approximate date of a tomb can be ascertained by studying

these costumes, particularly die head-coverings (see Plate XVII).

The head of the effigy in armour usually rests on his helm, while

a lion, No. 12, at his feet symbolises bravery. A dog, No. 6, at

the feet of a female indicates fidelity. Other symbols are two

wine-casks for vintners, and sheep or woolpack for merchants.

‘Weepers,’ Nos. 4, 5 and 9. Round the sides of some tombs are

small figures, technically known as c Weepers.’ They represent

the deceased’s family or relatives, angels (often having a shield

with coat-of-arms) and saints. On a few tombs of those who

BENCH ENDS

had founded a chantry or hospital are quaint little figures, No. 10,

representing ‘bedesmen’ (pensioners of the deceased whose duty

it was to pray for the soul of their benefactor).

‘Cadaver,’ No. ii. A gruesome fashion, of the 15th to 17th

centuries, portraying the deceased as a corpse, is found on a few

tombs.

Herse, No. 2. A bronze or iron erection around and above

some tombs of distinguished persons as a protection. At the top

were prickets for candles used at the anniversary .of the death of

the deceased, and at other times.

Mural Tablets, Nos. 7, 8, 13 and 15. Many of these contain

some good lettering and can be roughly divided into four groups:

the lettered panel surrounded by a carved frame, No. 8; the panel

projecting, with surrounding parts receding towards the wall,

No. 13 (with many in this group the ornament is more unobtrusive,

thus giving prominence to the lettering, the most important part

of these tablets); the third group consists of a more elaborate

architectural composition flanked by columns of pilasters, No. 7;

lastly there is the scroll-like ornament, often with cherubs or

cherubs’ heads, and helm, crest and coat-of-arms, No. 15. This

form is known as a cartouche.

BENCH ENDS

Bench Ends, Nos. 1, 7, 8, and 10 to 12. Fixed seats in churches

came into use in the 14th century, and were universal by the end

of the 15th century, when sermons were more important. In

early times no seats were provided. Congregations stood and

knelt during the services. When processions took place, the

verger headed them to clear a way through the congregation

scattered about the floor. The floor of the church was often bare

earth rammed down and covered with straw and litter. Some

churches had a stone seat, No. 13, attached to the wall for the

aged and infirm persons unable to stand during the services, and

this gave rise to the saying, ‘The weakest go to the wall.’ Early

seats or benches were made of thick oak planks, the ends plain

and flat-topped, No. 12; next, the tops were simply shaped, No. 8,

and later became more decorative, No. 10.

PEWS AND GALLERIES

‘Poppy Heads’ and Bench Ends, Nos. i to 4, 7, 8, 10, 11 and 12.

In the 15 th century, that age of great achievements by wood

workers, the bench ends were often richly decorated with carving.

Wood-carvers were given a free hand and showed considerable

imagination, with often a fine sense of humour. The tops of some

bench ends were finished with carved decoration known as a

‘poppy head,’ from the French word poupee. (puppet or figurehead).

These often took the form of weird animals, grotesque heads and

figures. Many wealthy people, in their wills, left money for

carved bench ends, so not only “poppy heads,’ but carved panels,

Nos. 7 and n, added to the richness of the effect. The subjects

carved were varied and interesting. No. 11, for instance, indicates

that the wood-carver evidently had a grudge against the Abbot,

for the top panel shows an ape inciting geese to rebel against the

Abbot (represented as a fox), while in the lower panel the fox is

handcuffed, with its feet in the stocks, and guarded by the heads

man (an ape with an axe). The prisoner’s mitre hangs on the

wall. Symbols of the Passion (see Plate XXVI) were carved on

some bench ends, and also used in stained-glass windows. After

the Reformation, the ruthless destruction, carried out by the

Puritans, of much of the beautiful 15th century woodwork led to

the loss of many of these lovely old bench ends.

Mansions and farmhouses near the church often had one or

more benches reserved for members of their household. The

names of these houses were carved or painted on the backs of the

benches, Nos. 5 and 6.

Maiden’s Garland, No. 9. At the death of a maiden in

Medieval Days a garland, consisting of real or imitation flowers,

with the maiden’s collar, glove or handkerchief attached, was

carried in the funeral procession and afterwards suspended over

the empty seat of the departed girl. Few of these remain in our

churches.

PEWS AND GALLERIES

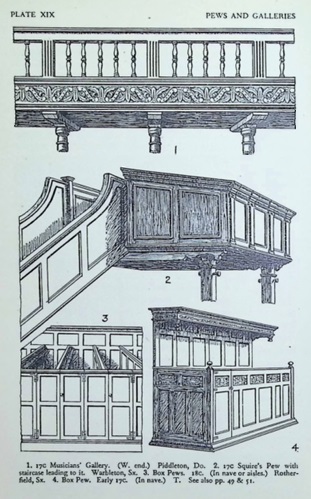

Musicians’ Gallery, No. 1. During the reign of Queen

Elizabeth, when she stripped our churches of most of the fittings

and objects used in Roman Catholic services, Rood screens (see

Plate XI) were taken down and many destroyed. Parts of them

PEWS AND GALLERIES